Part IX

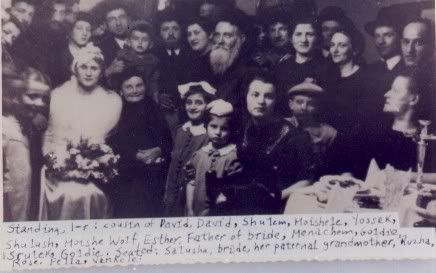

Rose Silberberg-Skier: They were amazed. They were amazed at my story. They were amazed that I could survive! That I could even escape! They couldn’t believe it! But they knew the terrain; they knew what I was talking about. And I said, that the aunt will come too. And I said there was another aunt, that will probably also come. And this policeman, Feder, will probably also come. And that’s what happened.

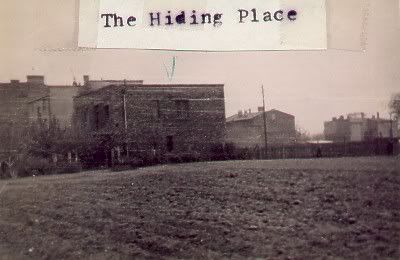

They all came, and then some other people…all total we were about seventeen people in that chicken coop. Can you imagine that? Unbelievable. Very crowded, but there was no choice.

DP: How did you spend your time there?

RS: My time was spent sitting doing absolutely nothing, because you were not allowed to talk. You were not allowed to move. Simply because she was living alone…and that neighbor, Dudwauka, was one in a million. She had nothing to do all day long. She used to sit at the window and watch the street. She knew everything that was going on on that block. And she disliked the Polish woman, Mrs. Cicha, particularly, because Mrs. Cicha was not Polish. She was Lithuanian. She was a Catholic, but she was Lithuanian.

And she was very modern, in that she was married, and her husband drank and used to beat her. So she divorced him. That was unheard of in Poland. Divorce?? So people said, “How dare you get divorced! When I get beaten up, and I don’t divorce my husband!” You know, they were really jealous of her. She was so independent!

And she remarried. The second husband was working in Germany. So she had no friends. So this Dudwauka, she hated her altogether. And she started to make these remarks like, “I think you have some Jews living with you…” This was the worst thing you could tell somebody. If you wanted to curse them, you would say, “You have Jews living in your house.”

And she used to say, “I don’t have Jews, because I don’t know any Jews. You have Jews but I don’t know Jews.” And this is how they used to fight. But still you had to be very careful.

So we were doing absolutely nothing. We used to whisper. It was very boring. My aunt told me (and I remember too), we had two slices of bread a day. That’s what we got. I used to cut them in a hundred pieces, each slice. And then, every ten minutes I would take a piece. So I ate all day long. And she was very angry, because she said, “If somebody knocks on the door, we have to hide, and they’ll find these pieces, and they’ll know somebody was here. Eat up and be done with it!” She had no patience just to watch me. Nothing doing. This was my occupation. Just to sit there doing nothing.

But in January 1944, suddenly, there was a knock on the door, and the Polish family that had taken my sister brought her back. And they said, they loved her, they loved her very much, but they said, “We have to bring her back, because she has brown eyes and brown hair. And that means she’s Jewish. And the neighbors are threatening us. They’re saying, ‘We’re going to call the Germans, you’ve got a Jewish child.’”

And this family said that this was a “niece,” because everybody knew that they only had two sons. “No, it’s a Jewish child, and we’re going to call the Gestapo.” And after a while they got very scared. So she was 4 years old, 4 ½.

Now, when she was taken away, at least a year and a half before, she was just a baby. But when she saw me, she ran over to me, and she said, “I am not allowed to say this to ANYBODY, but to you I will.” And right into my ear she said, “I’m Jewish, and my name is Malka. And you’re my sister Rozia.” She knew that too. I could flip out! She was so smart! I loved her! She was just amazing.

And she spoke (whispered) with a Polish peasant accent. The Jews never spoke like that. She sounded so cute! And she used to sing in a whisper. And knew all the words of songs, and everything.

I said later, even after the War, I said to my aunt, “How did she know that she’s Jewish?” A baby, of three? So my aunt said when she used to be the courier, she used to bring the money to pay off. Even when my father and mother were gone, they had left money, to pay for the Polish woman where we were hiding, plus for my sister. So she used to go once a month, and pay. And my aunt didn’t arouse any suspicion. She could move among the population. She was one of them.

So she said, “When I came there, once a month, I used to take her aside, and whisper to her a few things, like don’t forget who you are, and things like that.” Just in case we should all get killed, she should know one day. So she said she had like a booster shot.

DP: Did she recognize you when she first saw you?

RS: Immediately! She came over to me, she was running.

So this family…in fact they cried when they left, they said, “We’re so sorry!” And that Kazek, that boy, he was in tears. He loved that kid. “But we have to leave her, we cannot help it.” It wasn’t as if they had thrown her on the street. They brought her to her family, they brought her to the hiding place, and they left. And there she was with us.

Five weeks went by. In that time, the Polish woman brought us boxes, from cigarette cartons and we used to cut it up and make playing cards. These cards, my sister was sketching the animals, and I put the numbers in. Because she was like 4 years old. These cards were found after the war and they are now in the museum, and I will see them on Sunday. They are being exhibited.

At one time I remember she started to climb into the attic, back and forth, back and forth. This was just the day before she was caught, and I’ll never forget that I slapped her. And later I was so sorry that I gave her a big slap.

In February 1944 in the middle of the night, suddenly, there was screaming going on. The SS came to get us. At first, when she (Mala) was brought, there were two uncles, one from my mother’s side and one from my father’s side.

DP: What were their names?

RS: The one from my mother’s side was Samuel Klapholz, he’s the one from the NY Times (editor’s note: An article in the NY Times regarding life insurance policies taken out in pre-War Poland).

And I’d rather not mention the other one. Just that he was a Silberberg, but not the first name. This is what they did. They said just in case something happens, we have to make arrangements, as a precautionary measure. If someone knocks on the door, or the Germans come, that we should take care of these children. So Samuel Klapholz was going to throw me into the sub-bunker, and the other uncle was going to throw my sister. And then run off through the window. And close the bunker. And this they were even sometimes discussing with us. They said, “Look, if something happens, you go with Uncle Sam, and you go with this uncle. And they’ll throw you in.”

And this is what happened in the middle of the night in February. Terrible screaming going on. “OPEN UP OPEN UP OPEN UP!!” And the SS came in full gear, and just as they were coming, and we heard it (we were all sleeping, it was midnight), my uncle Samuel Klapholz took me, and threw me into that sub-bunker. He even took my Aunt Sara and another aunt into the bunker. And he ran out.

Now, the one who was supposed to take care of my sister panicked. He ran out, and he left her lying on the floor, sleeping.

We were in that sub-bunker. We could see everything through the slits. The SS came with full gear, with tremendous flashlights, and they were shining it right into her eyes and this is how she woke up. You’re talking about a four year-old child, waking up and looking at the SS, and she knew who SS are. And they said, “GET UP!!” And she saw this and she started to cry.

“Where is my sister!! Where is my Aunt (whom she knew)?? Where is my Aunt Sara, where is my sister??” And they said “Come on! You’re coming with us!”

I cannot tell you…I was there, just beneath…(breaks down)

This has haunted me all my life…I couldn’t help her…they were just grabbing her in her pajamas. They took her to prison…in February. You know what that was? She was just 4 ½ years old. I heard her say, “where’s my sister, where’s my sister” and she left.

They took the others too. They took Mrs. Cicha and they arrested her. And they took them all to Auschwitz. Except for my Uncle. After they had left, my Uncle Sam came back through the window, which was very brave, and opened that drawer for us and took us out. Because had he not done it, let’s say had he said, “Well why should I go back, if an SS man is waiting there?” Then we would have died there, we would have suffocated.

But he came. He was very brave. He opened it, and we all came out.

Now what happened to my sister, is that they were all going to Auschwitz. Mrs. Cicha was a Christian, so they separated the Jews from the Christians. She went to the Christian part of Auschwitz. They did not kill the Christians. Whatever they did, they definitely did not kill Christian children. This was never done that they would just round up [non-Jewish] children and kill them. They took the Jewish children with the adults.

But for a little while, for a few days, she was together with Mrs. Cicha. Before they separated, before they realized who was who etc. But the story goes, and after the war I heard from other people, and Mrs. Cicha, that an SS man heard that she could sing beautifully.

And he came, and he put her on the table, (and she was just a little kid), and he said, “Sing.” And she was singing. And he gave her candy. The next day he came back and he put her again on the table and said, “Sing.” And he gave her candy.

On the third day, he did the same thing. He put her on the table, he said, “Sing,” and as she was singing he took out a revolver and he shot her DEAD, right in the back of her head. He just blew her brains out. And he killed her. That’s what happened to my sister.

next